The "life-giving" public library & John Muir

- THIS IS AN EXCERPT FROM "THE UNCOVERING: A MEMOIR," PART OF A SECTION ABOUT MY HIGH SCHOOL YEARS.

- GO TO SELECTIONS FROM A MEMOIR FOR LINKS TO OTHER EXCERPTS FROM THIS WORK IN PROGRESS.

By Ted Trzyna

Copyright © 2021 T. C. Trzyna Citation: Trzyna, Ted. "The life-giving public library & John Muir." Ted Trzyna. trzyna.info. Posted January 2021

_______________

“More sacred and life-giving than school or church”

I explain in another part of this memoir that I went to South Pasadena High School and most of what I learned in those high school years, 1954 to 1957, took place around two other local institutions: the public library and the Boy Scouts. This page is about the library and what it led to.

Lawrence Clark Powell, the prolific writer and UCLA University Librarian who grew up in South Pasadena — I mention him below and elsewhere in this memoir — wrote that the South Pasadena Public Library was “more sacred and life-giving than school or church.” [1] I certainly agree.

Many of those who settled in what became South Pasadena were well educated and had a love of books. A Social and Literary Society was started in 1886. When South Pasadena became a city in March 1888 its leaders lost no time organizing an unofficial Lyceum, which opened in February 1889 with a free reading room and a circulating book collection. Then in September 1895, when the town had around 600 residents, the city council established the South Pasadena Public Library. It has been a center of community life ever since.

For me the public library was a short walk or bike ride from school or home, and most days I went there after classes. As I got older, I went there in the evenings instead. Rarely was this to do homework. Instead, I browsed the library shelves, found something of interest, and tended to read about the same subject for a week or two, one book leading to the next: California history and natural history, books by and about explorers of Africa and the polar regions, fiction such as Ernest Hemingway’s Nick Adams stories, based on his own youth. And highbrow magazines, especially The New Yorker.

Discovering the romantic in me

I became fascinated by W.H. (William Henry) Hudson, an author who was born and raised on a ranch on the Argentine Pampas. Hudson’s parents were New

Englanders who settled there to raise sheep and brought with them a 500-volume library. He ended up in England and late in life wrote Far Away and Long Ago, a memoir Ernest Hemingway recommended to young writers as a model of non-fiction. I wrote my senior paper on Hudson’s novel Green Mansions: A romance of the tropical forest (1904). Set in Venezuela, the story is about the last surviving members of a lost tribe who live in peace with nature and themselves.

I was discovering the romantic in me, not romantic in the sense of love, at least not yet, but romantic as defined by the dictionary as “marked by the imaginative or emotional appeal of what is heroic, adventurous, remote, mysterious, or idealized.”

Entrance to the South Pasadena Public Library as it was in the 1950s. Note the California authors' names inscribed below the roof-line: Josiah Royce, John Muir, Bret Harte, Richard Henry Dana. [SPPL]

_______________

CONTENTS

"More sacred and life-giving than

school or church"

Discovering the romantic in me

Images: W.H. Hudson, John Muir

John Muir

Muir's significance

Starting to build a library of my own

Outcomes

Images: Muir, Theodore Roosevelt

Above: The books mentioned and a sketch, W.H. Hudson, by William Rothenstein, 1920 [University of Toronto, Internet Archive]

Below (L-R): (1) The book that changed my life. (2) John Muir is looking right at us. Photo by Kraig, circa 1908 [University of the Pacific, Holt-Atherton Special Collections] (3) My First Summer in the Sierra, not published until 1912, follows A Thousand Mile Walk to the Gulf chronologically. (4) The Mountains of California includes a chapter about one of Muir's walks into the San Gabriel Mountains.

John Muir

A book I discovered on those library shelves changed my life. It was John Muir’s A Thousand-mile Walk to the Gulf (1916), an account of his traveling mainly by foot from Indiana to Florida, and then to California by ship with a crossing by rail of the Isthmus of Panama. This was in 1866-67 when Muir was turning 30.

I had seen Muir’s last name inscribed below the library’s roof-line along with the names of other famous California writers, but didn’t know much about him. I was attracted to this particular book because it was based on his daily journals and had a lot of detail about places and people so I could experience his trip vicariously.

How could I resist a book that started with Muir taking a ferry from the Indiana side of the Ohio River to Louisville, Kentucky, where he “steered through the big city by compass without speaking a word to anyone. Beyond the city I found a road running southward, and after passing a scatterment of suburban cabins and cottages I reached the green woods and spread out my pocket map to rough-hew a plan for my journey.”

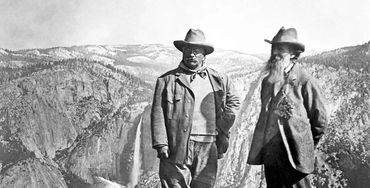

Born in Scotland in 1838 and raised in Wisconsin, John Muir became one of the founders of the American conservation movement. Once in California, Muir explored its mountains and wrote articles for leading magazines and newspapers about his experiences, urging protection for its extraordinary natural places. He visited and wrote about other places in the West and in Alaska. He lectured and lobbied. He co-founded the Sierra Club in 1892 and served as its President until his passing in 1914. He became friends with influential people and in 1903 famously camped alone with President Theodore Roosevelt in Yosemite for three days and nights. The outing had a lasting effect on T.R., who signed into existence five national parks, 18 national monuments, 55 wildlife refuges, and 150 national forests during his presidency, most of them after his time with Muir. T.R. also signed the Antiquities Act of 1906, which gives presidents broad authority to create national monuments.

On his way to meet Muir in Yosemite Roosevelt visited and gave speeches in South Pasadena and Claremont; see the photos at the bottom of the page.

Muir’s articles were gathered, often with new material, in books published by the prestigious Boston publishing house Houghton Mifflin, which also published Henry David Thoreau and Ralph Waldo Emerson. Among his books, most of which are still in print, are The Mountains of California (1894), Our National Parks (1901), and My First Summer in the Sierra (1912).

Muir is most closely identified with the Sierra Nevada, especially the creation of Yosemite and Sequoia national parks, but he often visited friends in Pasadena and explored and wrote about the San Gabriel Mountains. [2]

Muir's significance

Probably the most important thing Muir gives his readers is an understanding of the interconnectedness of all living things. He summed it up nicely: “When we try to pick out anything by itself, we find it hitched to everything else in the Universe.’" He wasn’t the first to write about the web of life; that was the German explorer and scientist Alexander von Humboldt, whose works had inspired the young Muir, but Muir’s writings and lectures spoke to a different audience, later generations fascinated with the American West.

The documentary film maker Ken Burns said of Muir, "As we got to know him ... he ascended to the pantheon of the highest individuals in our country; I'm talking about the level of Abraham Lincoln, and Martin Luther King, and Thomas Jefferson, and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Jackie Robinson — people who have had a transformational effect on who we are.” [3]

Lawrence Clark Powell, who I mention above as a kid growing up in South Pasadena, and who wrote extensively on California literature and its writers, including in California Classics (1971), said of Muir: “If I were to choose a single Californian to occupy the Hall of Fame, it would be this tenacious Scot who became a Californian during the final forty-six years of his life." [4]

I said the Muir book I found at the public library, A Thousand-mile Walk to the Gulf, changed my life. This is no exaggeration. Reading it led to my devouring other books by and about Muir and then reading as much as I could find about nature conservation.

Starting to build a library of my own

I wanted my own copy of A Thousand Mile Walk and it was out of print, so I took a bus downtown and went to Dawson’s, a bookshop then on Figueroa Street known for specializing in rare books about California and the West and mountaineering. It was founded in 1905 by Ernest Dawson, who knew John Muir and named one of his sons after him.

When I visited the store in the mid-1950s the sons, Muir Dawson and Glen Dawson, were running it and took time to talk to me about Muir Dawson’s namesake. Over the years I bought many more items from the Dawsons. In book circles in the 2010s I had the pleasure of meeting Glen again as well as Muir Dawson’s widow Agnes. Glen lived until the age of 103.

Outcomes

Reading John Muir led to my joining the Sierra Club, becoming one of its vice presidents and then chair of its International Committee, going on to leadership roles in IUCN, the International Union for Conservation of Nature, and in 2018 receiving the Sierra Club’s Raymond J. Sherwin Award “for extraordinary volunteer service toward international conservation.”

Reading books about Africa from the South Pasadena Public Library led to my taking courses about African history and politics at USC and UC Berkeley, serving as a U.S. diplomat in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and returning to the continent many times for my conservation work.

Reading about California at the library eventually led to my producing eight editions of The California Handbook, a standard guide to organizations and publications about the state, and carrying out many other convening, research, and publishing projects on California topics.

Visiting the South Pasadena Public Library almost every day led to a lifelong habit of stopping in at a public or academic library wherever and whenever that has been possible.

For me they are truly "sacred and life-giving" places.

_______________

Notes:

(1) See Elizabeth Pomeroy. John Muir: A Naturalist in Southern California. Pasadena: Many Moons Press, 2001.

(2) Powell is quoted in Ruth Apostol. Centennial: The South Pasadena Public Library: First hundred years 1895-1995. SPPL, 1995, 47.

(3) Ken Burns is quoted in the Sierra Club's online John Muir Exhibit (go to Media/Films): https://vault.sierraclub.org/john_muir_exhibit/default.aspx.

(4) Powell. California Classics: The Creative Literature of the Golden State. Santa Barbara: Capra Press, 1971, ch. 12.

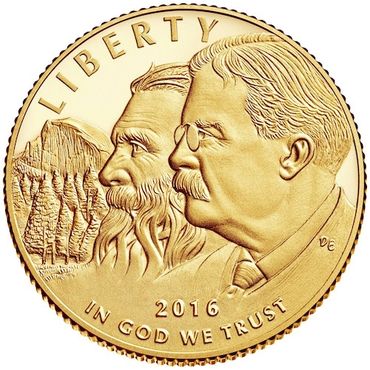

Images below (L-R):

(1) President Theodore Roosevelt and John Muir standing on Glacier Point, Yosemite, mid-May 1903. [National Park Service]

(2) Gold coin commemorating the 100th anniversary of the National Park Service with images of Yosemite's Half Dome, Muir, and T.R. [U.S. Mint]

(3) T.R. stopping for lunch in South Pasadena, May 8, 1903. Above him is a sign made of flowers that reads "Panama Canal"; at this time Panama was still part of Colombia and negotiations over access to the canal route had stalled. [USC Libraries and California Historical Society]

(4) T.R. speaking at Pomona College in Claremont earlier that day. [CC0]

(5) California quarter in the U.S. Mint's 50 States Series showing Muir, a California condor, and Yosemite's Half Dome. [U.S. Mint]